Business

The Case for E-Scooters as Public Transit

16 February, 2021

During the session “Pathway to Profitability: Moving Toward a Sustainable Shared Micromobility Model” at MM World conference, arisen the topic of the integration of shared micromobility services as public transport options. We discussed it with different participants, including Alex Nesic, who wrote this piece one year ago. To go further, you can also read this article from David Zipper and Marla Westervelt

Over the last 24+ months during the e-scooter boom, private sector companies with 4 letter names have regularly been at odds with cities and their regulators, ranging from mild frustration to all-out litigation and invocation of rather less polite 4 letter words. These relationships have been created by the familiar startup ethos to ‘move fast and disrupt’ in direct conflict with the public sectors’ typically slow moving and risk-averse approach to innovation. Clearly the approach is flawed; but is it the only way forward for the still nascent shared micromobility industry? I have some thoughts on the matter.

For the record, while a co-founder of Drover AI and prior co-founder of CLEVR Mobility, effectively a ‘veteran’ of this young industry, I am a part of neither the public sector planning literati nor the Silicon Valley Illuminati — just a passionate daily user of micromobility with an aversion to cars and some personal experience with gaps in public transit that would love to see cities embrace micromobility in a more integrated manner. Broadly speaking, I am advocating for transit agencies to incorporate scooters as an option in the greater multi-modal public transit ecosystem, allowing users to move freely between the various modes on their public transit payment card (or app for cities that have one).

First, some context

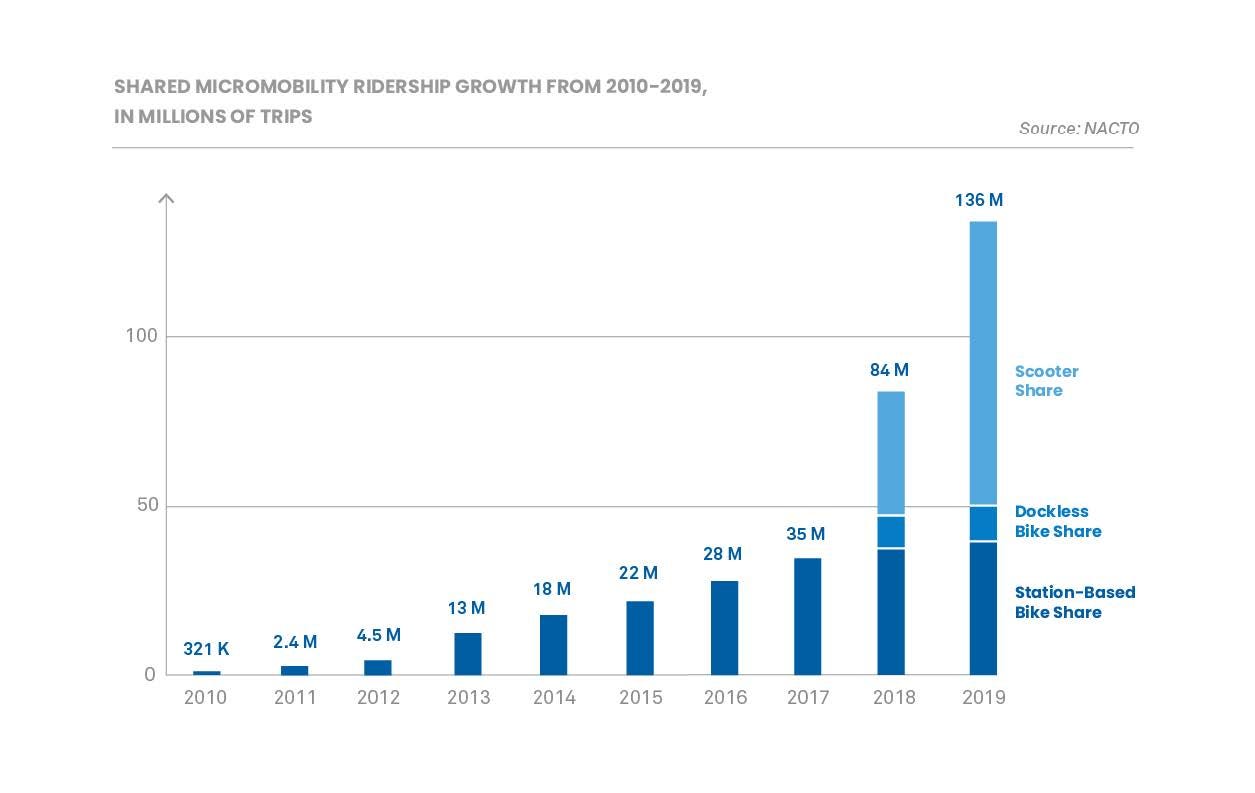

Public transportation’s purpose is defined in many ways, but a definition that I heard at a sustainability conference resonated with me: to provide affordable and equitable access to 4 basic universal needs — food, healthcare, education, and employment. More specifically related to micromobility is a perspective offered by Horace Dediu centered on 5 potential outcomes of any given trip — connection, recreation, activity, satisfaction, and the hunt. Historically, one of the biggest shortcomings of public transit has been the first/last mile (FMLM) problem. It is a very well documented issue, with cities even drawing up comprehensive strategic plans to address it, yet implementation (and integration) of solutions can be somewhat laborious (see LA’s delayed integration of TAP card with Metro Bikes). Docked bike-share systems are the veterans of the micromobility solutions to the FMLM problem, and have had varying degrees of success in different markets, often benefitting from time and heavy public (and private advertising) subsidies to survive, grow, and culminating in a total of 40 Million rides in 2019 according to a widely circulated NACTO report.

However, what is most striking about the chart above is not the impressive 40 million docked bike-share rides that took almost a decade to achieve, but the 88.5 million trips taken on electric scooters in just their second year in the market. This impressively built on the 2018 number of 38.5M scooter rides — it is safe to say that electric scooters and bikes combined to be a very popular addition to the micromobility landscape. Electrification is the single most powerful catalyst in driving this high adoption rate (as evidenced by the 15 rides per day average on electric CitiBikes in NY), with the novelty and more approachable form factor of scooters not far behind, all fueled by the convenience of dockless fleets.

Private sector solving public sector problems

While there are in fact numerous examples of the private sector doing things more efficiently and effectively than the public sector (see parcel delivery), transit is historically not one of them. Without taking a long-winded detour to argue this point, I would simply posit that the objectives of VC backed private companies are fundamentally at odds with those of a city or regional transit department. On the one hand, a private business must endeavor to turn a profit with their VC backers solely focused on the ROI and, on the other hand, cities have a mandate to provide transportation services to their constituents in an affordable, safe, equitable, and ubiquitous manner (even if affordable and ubiquitous are not profitable). Like Kanye and Taylor, these don’t often mix and when they do, it can get awkward.

This brings me to the permit framework most cities are using to manage dockless mobility. To their credit, cities have learned from the wild West early rideshare days and reacted much more Swiftly with scooters, but the permit structure remains inadequate for several reasons:

- Most cities do not have the staff or resources to properly manage and monitor the programs effectively.

- There is no guarantee that the fees imposed will be sufficient to cover the costs, further straining scarce resources.

- Even with permit allotment caps, cities usually have to manage multiple different operators — herding cats.

- The use of incentives/penalties to affect operator behavior and ensure equity is ineffective and rarely produces a consistent outcome.

- The data privacy leviathan inevitably rears its head (as with Uber/Jump in LA), creating additional troubles for cities, many of which are loathe to engage in protracted legal battles. By having multiple operators in each city, the current model effectively ensures that user data is spread across all operators (most users have all the apps), the aggregator(s) that cities hire to ingest the data feeds, and the cities themselves — that creates a lot of opportunity for data to be compromised.

In my view, the result has been some form of compromise where cities acknowledge the popularity and effectiveness of shared micromobility, while (somewhat reluctantly) attempting to regulate it — the approach reminds me a bit of an idiom attributed to individuals justifying not getting married: “Why buy the cow when I can get the milk for free!?” While in my analogy the ‘milk’ isn’t really free, cities have somewhat settled for allowing the private sector to choose the type of ‘milk’ they get.

A blueprint already exists

In 2019, the scooter industry came under much scrutiny for its unit economics and profitability (or lack thereof). While many reasons and potential solutions have been volunteered, the fact remains that blitz-scaled private shared micromobility is not profitable, and will likely not be for some time particularly in medium to smaller cities.

Enter the public sector subsidy, largely responsible for the historic successes of the automotive, fossil fuel, and (in a much smaller scale) the bike-share industries. As part of public transit, profitability is no longer the sole objective and the true potential of shared micromobility can be explored in relation to the broader urban transportation objectives. A growing number of cities agree that automobile decongestion and returning the public street space to people is beneficial to the public on many levels, so let’s invest public funds in transportation options that align better with that objective.

Many cities already have a working public/private framework in place in the form of bike-share — in LA for example, Metro Bikes is owned by Metro but operations are contracted out to Bicycle Transit Systems. Cities should supplement existing docked bike-share systems with dockless electric scooters and bikes. Capital expenditures spent on increasing non-electric bike-share fleets at low usage rates rather than investing in a more popular, electrified version of micromobility seems a bit like buying two-way pagers to improve communication in the smartphone era.

Some might say that investing in such a ‘new’ technology is not the right move for cities, but I would argue that the required investment is rather insignificant in comparison with more traditional transportation project costs. Consider that the global average cost of building (operations and maintenance aside) a subway line is reportedly $500 Million per mile (often much more in the US) and takes decades to complete, or that new buses cost anywhere between $500K — $800K each with up to $215/loaded labor hour to operate. In contrast, a high quality ‘fleet grade’ scooter costs approximately $400 — $650 and around $12 — $15 per day to support. Roughly speaking, a fleet of 1000 scooters could be acquired and deployed for one year at a cost of $5.5 Million.

Let them have scooters!

In an excellent piece on CityLab, Terenig Topjian makes the case for a bolder vision and much larger scale investment in micromobility infrastructure if we truly want meaningful mode shift away from cars. Ironically, before the automobile and oil industry co-opted public subsidies to underwrite their growth, cycling infrastructure projects like the Pasadena Cycleway were underway. There is, in my opinion, much to be gained by having cities also take more ownership in providing shared micromobility to their constituents as public transit options. The following are some of the advantages in doing so:

- In addition to being much lower cost than other public transportation projects, shared micromobility is also much more rapidly and flexibly deployed in response to demand.

- Cities can address gaps in their service and transit deserts, whether they are time or geography based.

- Cities would have the ability to ensure predictability and consistency of service through longer term programs. As evidenced by recent announcements by Lyft, Lime, and Bolt pulling out of markets like Atlanta and San Diego, private companies can choose to pick up their toys and leave whenever they choose — be it due to lack of profitability or onerous regulations. The ones that suffer most in these cases are the users that are left hanging.

- Integrated micromobility will drive traffic to existing modes of transit

- In Oakland, Lime reports almost 80% of trips either originating or terminating at a BART stop

- Data from CLEVR’s grüv scooter fleet in Oakland saw nearly identical results, also showing over 60% of total rides occurring in designated Communities of Concern.

- Cities can control pricing, saturation, deployment strategies and geographic availability with the goal of ensuring equity in the system.

- Cities would integrate scooters with current transit payment options. Multi-modal transit users would no longer pay multiple times across different provider platforms for a single journey.

- The data privacy issue is greatly mitigated — by contracting with a single operator and owning the system, cities would own the data and determine who (if anyone) has access to it. By running a fleet through existing transit payment systems that already offer anonymized payment/use options, the personally identifiable information (PII) conundrum is much less problematic.

- Micromobility would be the ‘gateway modality’ for new demographics of riders to get hooked on the broader public transit ecosystem. They start with scooters and before you know it, they’ll be using the light rail, subway and buses too…!

- The deployments branded as transit vehicles would be perceived as a service along with the rest of transit rather than a private sector intrusion and abuse of public right-of-way. I believe that shift in perception would substantially alter the overall public discourse for the better. (Side note, maybe I’m deluded, but perhaps vandalism would decrease and law enforcement would be more compelled to protect ‘public’ property.)

- If Cities want to accelerate the pace at which they can achieve their Vision Zero objectives, then incorporating scooters is a must to reduce the amount of traffic violence.

- Cities would be able to ensure that the workforce employed in support of these deployments are well payed W2 jobs rather than gig economy contract work.

- Cities would benefit from some of the non-transit related capabilities of these smart mobility devices. As ‘cloud-connected batteries on wheels’, these vehicles can also be equipped with a variety of technologies like environmental sensors to assist city management in measuring air quality, noise, and even gunshot detection.

Micromobility — it does a city good!

When evaluating whether shared micromobility might be a viable solution, I believe cities are already trying to do so in a way that best aligns with their broader goals, including accessibility, equity, affordability, ubiquity, and quality of life. Looking at it through that lens, cities might conclude that owning the proverbial cow may well work out better than relying on the private sector to provide the right kind of milk.