Cities, General

🇸🇦 Planning Micromobility : a Saudi Perspective

18 December, 2025

Attending CoMotion Global in Riyadh (December 7–9) confirmed that the Middle East—and Saudi Arabia in particular—is becoming a structurally important region for shared micromobility worldwide. Unlike Europe or North America, where shared mobility has evolved incrementally through demand-led experimentation, Saudi Arabia is deploying micromobility as a strategic planning instrument. National visions, giga-projects and large-scale public investment are shaping a market where shared micromobility is embedded upstream in urban design, tourism strategies and economic diversification agendas rather than retrofitted after the fact.

This shift is critical: It marks the transition from pilot-driven experimentation to platform-based deployment, where governance models, performance metrics and integration with public transport matter more than fleet size alone.

Current Market Landscape and Outlook

Over the past five years, shared mobility across the Middle East has evolved from isolated pilots into a structured and institutionally supported market. Ride-hailing remains the dominant shared mode, led by Careem and Uber, but micromobility has emerged as the most adaptable layer of the mobility ecosystem. Its low CAPEX requirements, rapid deployment cycles and suitability for first- and last-mile connectivity make it particularly aligned with the region’s accelerated urban development timelines.

Saudi Arabia reflects this trajectory. The national shared mobility market is expected to grow at double-digit rates throughout the coming decade, driven by Vision 2030 and a clear shift toward multimodal transport planning. Riyadh has become a primary test environment, with controlled e-scooter deployments in defined zones, such as the Sports Boulevard or Boulevard City, demonstrating how shared micromobility can complement the city’s expanding metro and BRT networks. These deployments are not designed as standalone services but as functional connectors within a broader mobility system.

Medina represents a more mature model with Careem Bike, Saudi Arabia’s first large-scale docked bike-share system. With 500 e-bikes and 60 charging stations, the system is designed to handle extreme demand peaks linked to pilgrimage flows, offering valuable insights into fleet sizing, resilience and user onboarding under unique conditions. Other destinations, including AlUla, have embedded shared micromobility directly into their masterplans, alongside autonomous shuttles, electric buses and tram concepts.

The Saudi market is currently led by local operators such as hopOn, BSKL and Spiders, with limited international presence, mainly from Dott in Saudi Arabia and the UAE. This creates a distinct competitive landscape where local operational expertise, regulatory alignment and infrastructure adaptation often outweigh global brand scale.

At the regional level, Dubai and Doha serve as reference points for governance and regulation. Dubai’s licensed multi-operator model and Careem Bike network have demonstrated how scale can be achieved under strict regulatory control, while Doha’s deployments—supported by academic research—offer valuable insights into demand behaviour under extreme climatic conditions. These precedents increasingly inform Saudi regulatory expectations, which now emphasise safety, performance KPIs and system integration. Overall, the outlook points toward sustained growth, deeper public transport integration and gradual adoption of MaaS frameworks.

Local Constraints and Market Specificities

Saudi Arabia’s micromobility market presents structural constraints that differ significantly from Western contexts. Climate is the most immediate factor shaping operations. Extreme heat, high solar exposure and, in coastal cities, humidity compress demand into early mornings, evenings and night-time hours for much of the year. This directly affects vehicle specifications, battery performance, charging strategies and fleet rotation models.

Operators such as hopOn, active in Jeddah, AlUla and NEOM, have responded with solar-powered stations providing shade and off-grid charging—an essential adaptation in remote or infrastructure-light environments. These solutions illustrate how micromobility in the Middle East requires infrastructure co-design, not just vehicle deployment.

Seasonality is further amplified by pilgrimage flows. The Hajj period creates extreme but predictable demand peaks, particularly around Makkah. Shared micromobility has proven highly effective for operational staff and service workers navigating congested zones, leading some providers to deploy entire fleets under temporary service contracts. The consistent year-on-year increase in usage during these periods confirms micromobility’s relevance in high-intensity, congestion-constrained environments.

Urban form remains another defining constraint. Decades of car-oriented planning have produced fragmented active mobility networks, limiting spontaneous micromobility use to high-footfall areas such as promenades, tourism districts, mega-projects and university campuses. As Ghassan Jaber, Country Operations Manager at Dott in Saudi Arabia, observes, “major urban projects are currently the primary drivers of shared mobility adoption. However, city authorities—particularly in Riyadh—are now pursuing long-term masterplans aimed at reconnecting urban fabric and building continuous pedestrian and cycling infrastructure”.

At present, micromobility is still predominantly used for leisure, often by families and groups in controlled environments. From a behavioural perspective, this is a critical transition phase: leisure use in safe settings is laying the groundwork for broader acceptance of shared micromobility as a reliable A-to-B transport mode.

Cultural and governance factors further shape deployment. Family-oriented travel patterns, evolving gender norms and the need for highly visible safety measures all influence adoption. Regulatory governance is typically centralised and aligned with national strategies, with clear expectations around geofencing, safety standards and performance monitoring once services are authorised. For operators and cities alike, success depends on professionalised operations and strong public-private coordination.

Mega-Projects as Catalysts for Growth

Saudi Arabia’s giga-projects are not simply demand generators; they are structural accelerators for shared micromobility. Designed as integrated urban systems from day one, these developments allow micromobility to be embedded at the planning stage rather than retrofitted later.

Diriyah exemplifies this approach. Conceived as a walkable, human-scale heritage destination, it places public realm and low-carbon mobility at the centre of its masterplan. Shared micromobility is expected to operate as a primary internal mode, integrated with on-demand shuttles and digital mobility platforms, supported by purpose-built infrastructure and clear operational rules.

NEOM—and THE LINE in particular—represents the most ambitious mobility vision globally, but also one of the most complex to deliver. While initially envisioned as a fully realised car-free linear city, the project has faced challenges related to cost, phasing and technical feasibility, leading to a more incremental delivery approach. This limits short-term deployment at scale but reinforces the need for modular, adaptable micromobility solutions aligned with phased construction.

From a shared micromobility perspective, NEOM is best understood as a long-term experimental framework. Its emphasis on automation, digital twins and performance-based mobility planning continues to influence design standards across Saudi Arabia. Importantly, NEOM’s workers’ camps already function as real-world testbeds: private vehicles are prohibited, making shared micromobility the backbone of daily transport. According to Nezha Jamjoom, Co-Founder and CCO at hopOn, the exclusive bike and scooter operator on site, “ this is currently the most successful micromobility market in the Kingdom, with average utilisation reaching 11 rides per vehicle per day. These results are already informing NEOM’s broader mobility strategy toward a sustainable multimodal model”.

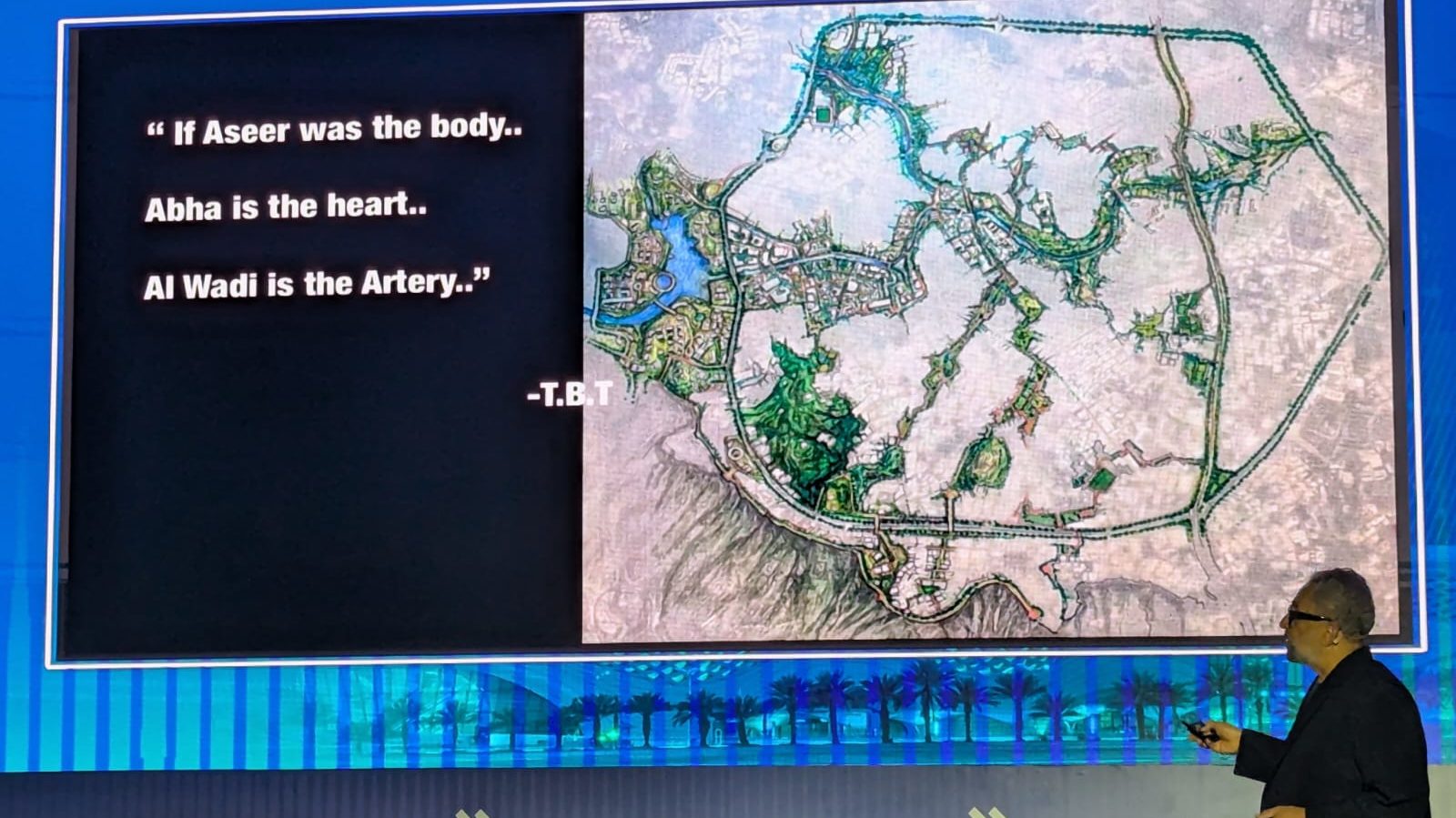

In the Aseer region, the AlWadi regeneration project in Abha highlights how micromobility can thrive beyond major metropolitan areas. With a cooler mountain climate and a tourism strategy targeting ten million visitors by 2030, AlWadi offers favourable conditions for leisure-oriented micromobility and short-distance travel. By integrating pedestrian corridors, cycling infrastructure and shared mobility nodes from the outset, it represents a new generation of tourism-led, low-carbon mobility environments.

Saudi Arabia is moving decisively from micromobility pilots to scalable, system-level deployment. Giga-projects are setting new operational and design standards, while major cities are laying the groundwork for network integration and behavioural change. For public authorities, developers and operators, the Kingdom offers a rare opportunity to design shared micromobility as infrastructure, not as an afterthought. It also represents a living laboratory where climate adaptation, governance models and integration strategies developed today will shape the next generation of shared mobility globally.